Heating applications influence the battery life of heated wearables, bending the shape of the electrical power demand requested, controlled, and constrained by the controllers and battery protection systems instead of directly consuming electrical power. To begin with, it is important to explain that heating applications do not consume batteries themselves; they are simply interfaces transmitting the instructions and commands to the hardware. The inherent basis of battery life is the power required by heating elements and internal system limits placed on controllers and batteries. One of the myths is that heating apps drain the battery just like video streaming apps on a phone, although, in fact, the heating elements themselves normally use a lot of power, and the app only has an indirect effect on power requests. Heating applications can only influence the battery life by rendering the request and management of electrical power to the heating system.

This knowledge is vital to the owners of the heated apparel brand, OEM, product managers, technical buyers, sourcing managers, and developers that need to consider or develop app-based heating systems. Through a discursive analysis of the interaction between software instructions and hardware reactions, we can cut down the mystery as to why the performance of batteries in warm wearables is frequently determined not by the individual features of an app, but by the holistic design of the system.

What Actually Consumes Power in Heated Wearables

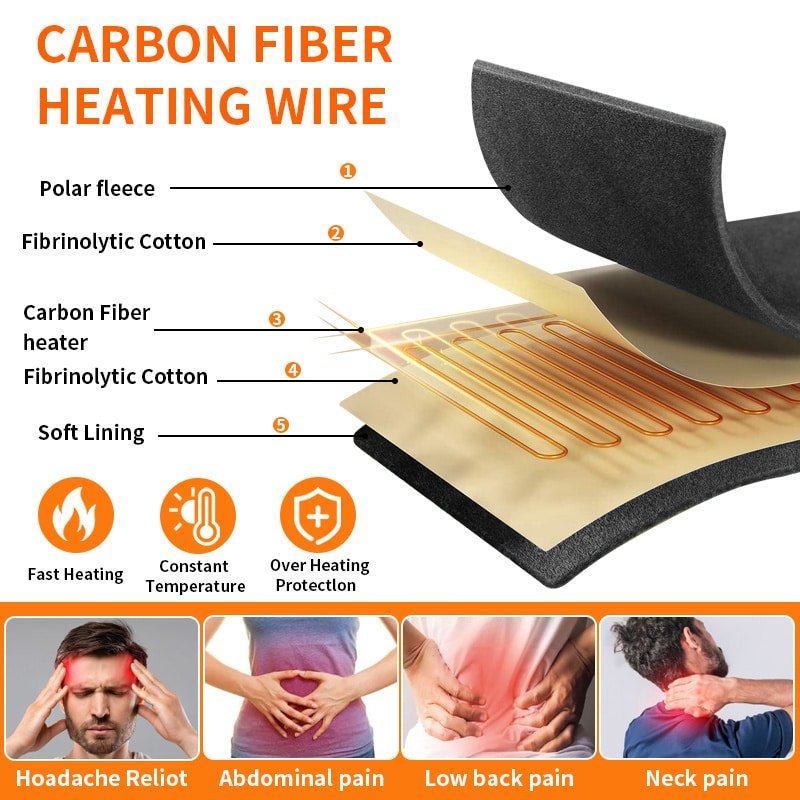

The heating components are the main component in power consumption of wearable gadgets as they transform electrical energy into thermal energy, which is much greater than any other component. The capacity of any battery in any app-controlled heated piece of clothing is divided among a number of subsystems, yet the heating itself consumes the majority of the usage. An example is that in carbon fiber or wire heating pads, constant current is maintained in order to heat, typically consuming several watts depending on the material and size of the area covered. Signal processing and communication is done through controllers and Bluetooth modules, which consume little energy compared to others, particularly when not in use they are usually in low-power modes.

An example of one way to break down estimated relative power usage in a hot wearable system is shown below:

| Component | Relative Power Consumption |

| Heating elements | Very high |

| Controller / PCBA | Low |

| Bluetooth module | Low |

| Mobile app | Negligible |

This table explains why the main emphasis on the app excludes the dominance of hardware. Heating devices may take 80-90% of the overall power when in use, and the input of the app is in the form of infrequent data transfer via Bluetooth, which is by several orders of magnitude lower. To reduce the total drain, engineers formulating these systems should focus on materials that are efficient in heating and insulation so that the battery functions of the wearable technology can be used in cold conditions as per the expectation of the users.

Major Power Consumers Explained

Going into further detail, heating components are the predominant parts since they are based on resistive heating, in which P = I 2R. This is increased by higher heat settings resulting in exponential consumption. Conversely, the microcontroller unit (MCU) and power management integrated circuit (PMIC) of the controller consume energy in activities such as pulse-width modulation (PWM) to control the amount of heat produced. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) versions are even more efficient, in that they go to sleep between linkages, making their effects less significant.

The mobile app, which operates on a separate device such as a smartphone, does not use the battery of the wearable in the least its power necessarily influences the wearable to execute specific instructions to the controller of power delivery. This indirectness ensures that queries such as does heating app drain battery can be a misapproach towards attributing the problem, when it is actually the constant power-on to elements by app-initiated settings.

How Heating Apps Influence Power Demand Indirectly

Heating applications influence the power demand indirectly by providing users with an opportunity to choose the parameters indicating the level of the electrical flow intensity and the time of electric heating. The app does not directly consume energy, instead, it serves as a user interface that converts the input into a signal sent over Bluetooth to the wearable controller like temperature levels or timer. The power supply is then modulated by this controller to acceptable levels, though within an established hardware limitation to avoid overloads.

As an example, a user may choose a high heat setting in the app, which sends a command to the PWM signal to change the duty cycle to a higher level, i.e. the heating elements are powered during longer intervals of each cycle. This increases the overall power consumption without the application consuming any battery resources on a wearable device. This is further affected by duration settings such as auto-shutoff timers which restrict the overall amount of time spent on operation, in effect extending the battery life should they be programmed conservatively.

This is important in the app logic, which would include dynamic demand adjustment through ambient temperature sensor feedback. In a smart heating app control system, but due to its indirect nature, app updates or optimizations do not have a direct impact on the efficiency of the heating system but rather have a direct impact on the usability of the heating system. Developers who incorporate such systems need to simulate such interactions in their prototyping to determine the dynamics of such a battery in a real-world.

App Logic and Duty Cycles

Technically, app-selected heat levels are associated with a particular voltage or current goal. The low mode may have a 20 percent duty cycle (on 20 percent of the time), and high may be 80 percent, and energy consumption is directly proportional to these. The long term implications such as power consumption of heating applications are no longer of concern as the app is executed outside, but rather the efficiency of BLE packets reduces overhead in command transmission.

Relationship Between App Commands and Controller Power Regulation

Heated wearables have controllers that do the same but apply power control to ensure system stability and safety. When an application makes a command request such as turn up the heat, the firmware on the controller will compare it with internal settings such as maximum sustainable current or voltage. In cases where the request is too high, the controller puts a limit on it, and thus the excessive drainage is avoided irrespective of the purpose of the application.

This rule is based on the PMIC of the controller which provides feedback to control battery voltage and current in real-time mode. An example is when the app requires all the power, and the battery has 50% capacity then the controller may reduce the output to prevent the deep discharge to save on longevity. This interplay ensures that app control in heated wearables prioritizes hardware integrity over unchecked user inputs.

Command Interpretation Mechanics

App commands are normally encoded as BLE characteristics, the value of which, such as heat level=3, is a given frequency of PWM. These are processed by the MCU on the controller, with filters used to make the movements smoother and eliminate spikes, which can put a strain on the battery. The OEMs need to measure this at the design stage so as to achieve a balance between responsiveness and efficiency.

Common Battery Drain Scenarios in App-Controlled Heated Clothing

Battery drain in app-controlled heated clothing is a common issue in which a scenario of high power requirements coincides with the environmental or usage conditions, resulting in a more rapid-than-anticipated depletion. The use of high heat levelsuch as the maximum use of current to the elements increases discharge rates proportionate to the intensity of the setting. This is worsened by continuous operation with no pauses as batteries do not have time to recover, whereas cold conditions decrease the efficiency of electrochemical processes which is essentially a shortening of the run time.

The following is a table of common scenarios and their effects on the battery life of the controlled heated clothing when using the app:

| Scenario | Battery Impact |

| Maximum heat setting | Rapid discharge |

| Continuous heating | Predictable drain |

| Extreme cold | Reduced battery efficiency |

These scenarios underscore why battery drain app-controlled heated clothing requires a systems approach. Lithium-ion batteries implement reduced internal resistance at extreme temperatures, resulting in a reduction of effective capacity by 20-50 per cent below freezing, regardless of app commands.

Real-World Usage Factors

Drain is aggravated by the behavior of users, including failing to switch settings off after warming up. These are to be tested by simulating in order to be sure of the real performance by the technical buyers.

Why Battery Protection Logic Limits App Control

Protecting against failures Hard limits on app control are enforced by battery protection logic in heated wearables, which overrides commands when there is a risk such as over-current or overheating. An example of over-current protection is the current-sensing resistors that sense spikes and interrupt the power in case any thresholds are violated to avoid short circuits. Low-voltage cutoffs are activated below a programmed voltage (e.g. 3.0 V in the case of lithium cells) to prevent irreversible damage to the cell through over-discharge, but temperature is monitored by thermal protection, activated by inhibiting or shutting off elements when they get too hot.

This reasoning is reliable but may infuriate the user that accuses the application of not responding. The actual fact is that it is actually a design decision to increase the battery life and adhere to the safety regulations.

Protection Mechanisms in Detail

In-built over-temperature protection, which is usually part of the controller, is an algorithm that predicts the presence of heat. For more on over-temperature protection heated wearables, take into account the interaction of this technology with app feedback.

How Brands Should Evaluate Battery Life in App-Controlled Wearables

Brands that consider the battery life of their app-controlled wearables ought to focus on system level testing than theoretical specifications because real life variables such as usage patterns and environments demonstrate the actual performance. System testing is a process that entails the prototyping of the system under test by cycling the prototypes through simulated profiles: mixing the heat levels, duration and temperature to measure the actual milliamp-hour (mAh) consumption versus the rated capacity. Significance is found in developing actual use profiles that are a replica of the end-user behaviors, including intermittency of heating when performing outdoor activities, as opposed to the continuous lab conditions.

These should be taken into consideration in OEM battery capacity planning, where the cells are chosen based on the right C-rates (discharge capabilities) and headroom is added to allow protection overhead. To take the example of a 2000mAh battery, an effective capacity of 1500mAh may be achieved after considering the inefficiencies and these figures can be used to size a battery to achieve certain run times such as 4-6 hours at medium heat.

Evaluation Best Practices

Add accelerated life testing (ALT) to forecast long-term degradation, so that the apps will show the correct remaining battery estimates using calibrated models. This level of reasoning which is on the OEM level prevents overselling on specifications.

Conclusion — Battery Life Is a System Outcome, Not an App Problem

The heating apps have an impact on the battery life because they determine the way the power will be requested and controlled, yet the real battery performance depends on the heating demand, controller limits, and battery protection logic. This system relationship is critical in the assessment and design of effective wearables in the form of heating. The behavior of users is crucial, including the choices of suitable settings to be used in the environment, as well as the design of a strong hardware that is efficient and safe at the same time. Thinking of battery life as a systemic effect and not a solitary aspect of the app will help brands and engineers devise a solution that provides consistent warming functions without unforeseen disruptions.